Status Symbols are devices that transcend their specs and features, and become something beautiful and luxurious in their own right. They're things that live on after the megapixel and megahertz wars move past them, beacons of timeless design and innovation.

In 2003, Nokia made the world’s three most popular phones. They were all short, stubby candy bars, with nine buttons and a tiny monochrome screen. All three looked and worked like every other cellphone on the market, but they were $50, or $20, or free. So they sold like like crazy.

But early the next year, underneath a glass case inside the Arken Museum of Modern Art in Copenhagen, a select group of 110 fashion journalists got an unexpectedly high-tech glimpse at the future. It was the Motorola RAZR V3, the cellphone that would change the world.

Jim Wicks, Motorola's head of design since 2000 or 2001 (he can't remember exactly), says changing the world was the plan all along. "At the time, all cellphones had started to turn into these handy, nondescript, amorphous things. So the idea of going out and doing this thing that was very, very different would cut against everything everyone else was doing with handsets at the time."

Motorola was determined to be 'the king of thin'

Motorola started the project with two directives, mantras even. Wicks and his team were obsessed with being "the kings of thin," and making "no compromises." Those things sound obvious today, but were surprisingly counterintuitive a decade ago. Not to mention hard to do: in the process of creating the thinnest phone on the market, Motorola had to invent and refine technology after technology. Wicks wanted the phone to be made of metal, "high-quality metal. Not just stamped cheap stuff." But metal causes reception problems, so Motorola rewired the device so all the antennas and processing were in the bottom of the phone. The now-infamous RAZR chin was born of necessity, not design sketches.

Even the keypad was reimagined in the name of millimeter-shaving. "All the keypads had started to get really small," Wicks says. "And when you put a bigger keypad in there, you don't want those typical keypads with the baubles and the domes and all that — that alone would take up 5 or 10 percent of the thickness of the device. So that drove the innovation around the super-flat keypad, but if you do a super-flat keypad you can't do one of those membrane, plasticky things. So we did a metal one."

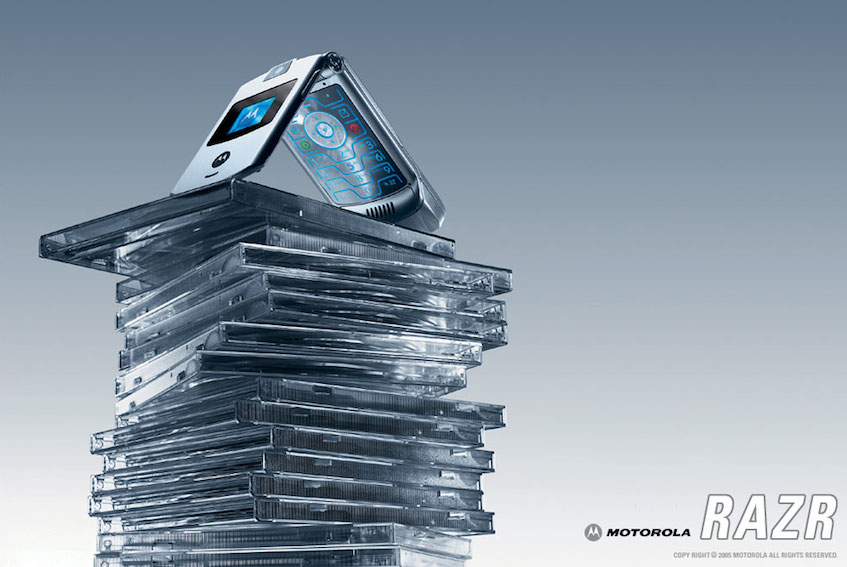

The phone looked and felt like nothing else on the market. RAZR wasn’t made to sell millions, but simply to prove what Motorola could do. Wicks says "when you showed carriers, many were like, ‘No. This isn't going to fly.' Plenty of people were interested, but it wasn't like they were all signed up for it." The phone was $449, a price virtually unheard of. Reviewers called it a fashion item, a curiosity.

The RAZR was strange, different, and expensive, but it was cool

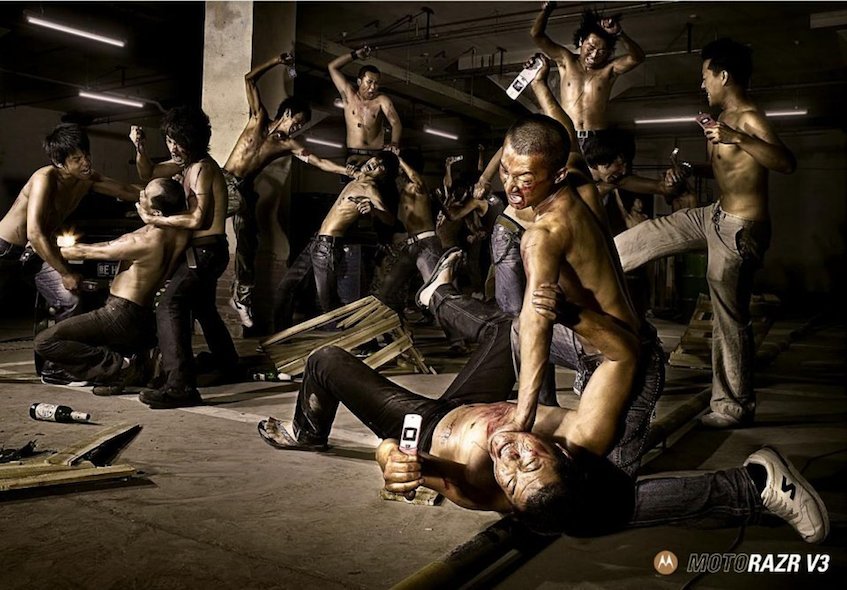

But as Wicks discovered in Copenhagen, the RAZR had going for it the only thing that really mattered: it was cool. The phone showed up in gift bags at the Oscars, in ads with Maria Sharapova, in Jason Bourne's pocket, and as a Monopoly token. It was, Wicks says, the first device to become something more than just a cellphone — a message Motorola drove home with a massive, relentless advertising campaign. "This is the first device that really moved it from being a communications tool to being a true consumer product, and actually a fashion product." USA Today's Ed Baig likened it to an expensive watch or a sports car — no one would buy the RAZR for purely practical reasons, he said, but if you could afford it there was no competition.

In 2005 and 2006, everyone I knew either had a RAZR or wanted one. My Voicestream Wireless-powered Motorola T193 was one of the legions of faceless candybar phones, but my friends' RAZRs were like something out of a Philip K. Dick novel. They were so thin, so well-machined, so dangerously edgy.

For years, all that had mattered was price — carriers sold their phones as cheaply as possible in a desperate attempt to sign up more subscribers. The RAZR kicked off a new era: Motorola proved that people would pay good money for great hardware. And with no app stores or great operating systems to compete with, there was only hardware, and no one could match Motorola. Many tried, from Sanyo's Katana (which aped even the blade-inspired name) to Samsung's SGH-A900, but no one came close. In a period of dominance unsurpassed before or since, for 12 straight quarters between 2004 and 2008, the RAZR was America’s best-selling cellphone.

The RAZR's success made Motorola blind to the coming of the smartphone

But while it rode the crest of the RAZR wave, eventually slashing prices and margins to keep the device flying off shelves, Motorola missed the coming of the next phase of cellphones: software and services. "We didn't look at what's going to disrupt [the RAZR]," Wicks says. "Someone else was. We didn't invest in disrupting our own leadership." And even when Motorola did try to evolve and improve, it met resistance from the all-powerful carriers. "We got caught in that bad spot where we were locked into our next-generation product lines and specs based on everyone saying ‘we want the same thing,' and once we were locked in everyone started to say ‘yeah, but that looks just like the RAZR.' Then the iPhone came out, and marked another shift in the phone industry."

Smartphones killed the RAZR once and for all, but it didn't have to be that way. Wicks points to the Ming lineup of handsets Motorola launched in China in 2006, a dual-screened flip phone with stylus input and handwriting recognition that could have given Motorola a new life in a screen-filled market. "It was one of our most unknown, but most awesome products," he says. But Ming devices never came out anywhere else, and the iPhone then all but decided what the next generation of phones would look like anyway.

Motorola was the first company to prove design could sell a cellphone, and for three years, an eternity in the consumer electronics world, it couldn't be stopped. The landscape may have changed since then, but the lessons Wicks and his team learned haven't. Motorola learned that companies have to excel at engineering, design, and marketing, he says, or they've got nothing. Design is the hardest, and most important: "If you do great engineering without doing great design, you're not going to be doing well at all."

The RAZR is gone, the flip phone basically obsolete — though Wicks won't rule out a comeback for the form factor. "I think technologies will evolve. I mean heck, if you don't have to touch the phone to use it…" He trails off. Suddenly I think we're both dreaming about a flip-phone Moto X.

There are 130 million former RAZR owners who might get very excited about that idea.